SU celebrates landmark birthday, reflects on SU’s 144-year architectural history

In a 1953 Post Standard article, Syracuse University’s campus was described as a “classic example of hodge-podge in architecture.”

Since its opening in 1870, it could be said that SU has thrived on this hodge-podge — not only in its architectural style, but also in its acceptance of all genders and races.

SU’s founders worked tirelessly to establish it as a model for an “American College”: an eclectic campus, with buildings to be constructed in wide-ranging architectural styles, hoping that it would be reflective of the inclusivity they preached from the beginning, the hodge-podge SU is famous for.

The Board of Trustees signed the university charter and certificate of incorporation on March 24, 1870. This day will be celebrated nationwide on Monday, signifying the university’s 144th birthday, but also as a reminder of how much it has grown since being just a few buildings on the Hill.

SU was founded as a Methodist school. Tuition in its first year was $20, and $10 for sons and daughters of Methodist ministers, said Mary O’Brien, who has been an SU reference archivist for more than 40 years.

Being a Methodist school meant that its doors were open to all from the very beginning. “People always ask, ‘When did you first allow women in, or when did you first allow minorities in?’ The answer to both of those is always,” O’Brien said.

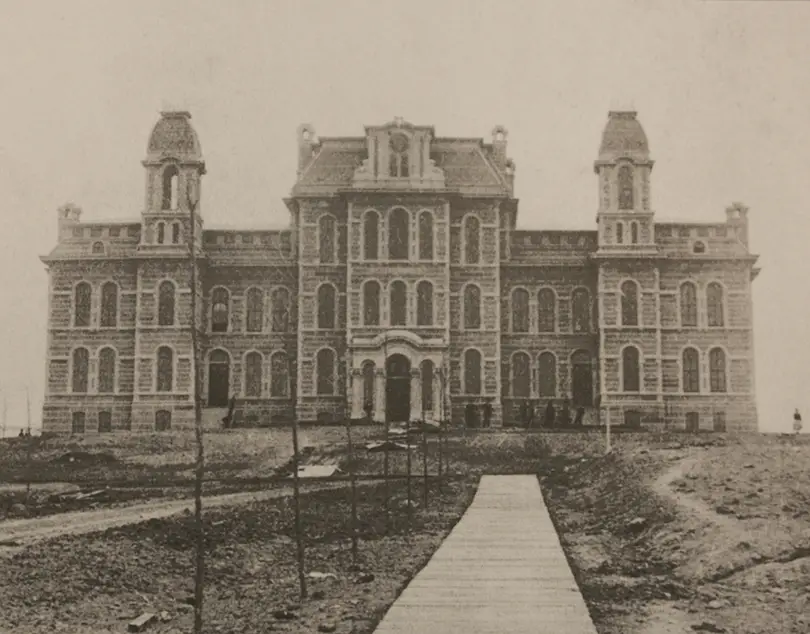

While the Hall of Languages was being built on University Avenue, classes met in the upper floors of a building downtown in what was called the Myers block. Classes continued there until the Hall of Languages was opened in 1873.

At the faculty’s inauguration in 1871, the Rev. Jesse Peck, then-president of the Board of Trustees, made the founders’ intention of inclusivity evident in his speech.

“The clear and well defined purpose of the trustees (is) that there shall be no invidious discriminations here against women or person of any nation or color,” Peck said. “Brains and heart shall have a fair chance, and we propose no narrow-minded sectarianism.”

The first graduating class at SU was comprised of one woman and four men. Mary Huntley was the woman. She later became a teacher after earning her masters’ degree from SU in 1875.

Their gradation was in 1872, after only two years of attendance. Once admitted, students were tested and placed in different grades depending on how much they already knew.

The Hall of Languages opened its doors in 1873 after two years of construction. The iconic building received its name as part of an original construction plan, which involved halls of math, science, history and others.

In 1873, SU also founded the College of Fine Arts — now the School of Visual and Performing Arts — becoming the only college to grant four-year fine arts degrees in the country.

However, SU was hit with an economic downturn in the midst of the Panic of 1873 that hindered further construction, and the Hall of Languages was the only building on campus for 14 years. O’Brien said SU barely held on financially.

Almost all of the first chancellors faced economic problems.

“They had great ambition, but because money is money, they had to scale back,” O’Brien said.

From then on, the development of new buildings at SU and styles of architecture became dependent on the funds and styles of several commissioned architects. The hodge-podge of architecture was becoming clear, yet even so, a pattern began to emerge.

During the late 1880s, the first buildings to follow the Hall of Languages were constructed: Holden Observatory, Von Ranke Library — now Tolley Humanities Building — and Crouse College. Together these buildings created a row of Romanesque style architecture on the South side of University Place.

John Archbold, a member of the Board of Trustees, recruited James Day to be SU’s fourth chancellor. Because Archbold liked Day so much, he would fund whatever Day needed if he took the job, O’Brien said.

When Day became chancellor in 1894, SU had five buildings. With funding from Archbold and others, 22 more went up by the time he left, including Carnegie Library and Archbold Gymnasium. By the time he retired in 1922, enrollment increased from 777 to 6,422 students.

In 1900, Winchell Hall became the first dormitory on campus, named after Alexander Winchell, the first chancellor of SU. Until then, students lived in sorority or fraternity houses, rented in the city of Syracuse, or lived with their families. Winchell Hall was torn down and replaced by the Schine Student Center in 1984.

After World War II, the enrollment at SU increased even more, O’Brien said.

“The university was growing in leaps and bounds, they needed buildings and they needed buildings quickly,” she said.

To try and meet SU’s growth spurt, O’Brien said the university built Booth, DellPlain, and other halls, which were “basically brick rectangles.” Donors also had an influence over the nature of the buildings — they were “putting their wallet on the line,” she said.

But above all, SU has shown a reverence for the past.

In 1979, the Hall of Languages was either going to be torn down or majorly renovated. The entire building was gutted and given a brand new interior, with very few alterations made to the outside.

Until 1991, Holden Observatory was located where Eggers Hall currently sits. When Eggers Hall was planned to become a companion building for Maxwell, Holden Observatory, at 320 tons, was moved 190 feet across campus at four inches per minute.

Today, more than 126 years later, the historic Holden Observatory still stands. And just like its founders intended, the Hall of Languages remains as a heart of academics and an iconic image of the Hill.

Said O’Brien: “(SU) would never have any intention of knocking down such iconic buildings. We’re advancing, always advancing, but yet with a never failing respect for the past.”

Published on March 24, 2014 at 2:37 am

Contact Lydia: [email protected]