Paint the town: ‘Sign Painters’ director discusses documentary, effect of art in cities

Whether it was painted yesterday or been left lingering on a brick wall, slightly faded from 60 years of exposure, a hand-painted sign tends to last and brings a sense of endurance to local communities.

“The most important thing is an idea of permanence,” said Faythe Levine, director of the documentary, “Sign Painters.” “There is an investment that people are going to be there and that we’re not all just opening businesses that are going to disappear in two years. People are investing time and energy into their local space.”

Levine, born in Seattle and now living in Minneapolis, is a painter, pioneer of the do-it-yourself art movement and filmmaker. Her credits include “Handmade Nation: The Rise of D.I.Y, Art, Craft and Design” and “Sign Painters,” a film about the “death and rebirth” of sign painting as an American art form.

Levine was at the Red House Arts Center on Monday to screen “Sign Painters,” her most recent documentary, which was co-directed by Sam Macon. The event was co-hosted by Echo, a local collective that provides studio space for artists in Syracuse, and the Near Westside Initiative, whose goal is to use art and technology to revitalize the Near Westside neighborhood.

The film features more than 20 artists from across the country reminiscing about the sign-painting “glory days,” which began when companies started branding themselves and needed to create logos. Brand-name replacements soon took the place of general stores, and sign makers thrived.

Without any third-person narrative, Levine uses only the painters’ voices to express what it was and — to a lesser extent — still is like to paint signs for a living. Virtually no one was in the business to get rich, Levine said after the event. But anyone who tried it ended up loving it for the freedom it offered. Sign painting even garnered its own group of followers called Letterheads, or people heavily invested in the art form.

“You know the motto, don’t you?” said the late Keith Knecht, a sign maker from Toledo, Ohio, in an interview during the film. “IOAFS: It’s only a f*cking sign.”

That nonchalant attitude was present in every interview showcased in the film. Sign painting was about having fun, each artist said. But as new technologies were introduced and signs swayed toward the cheaper vinyl prints, painters lost a lot of business.

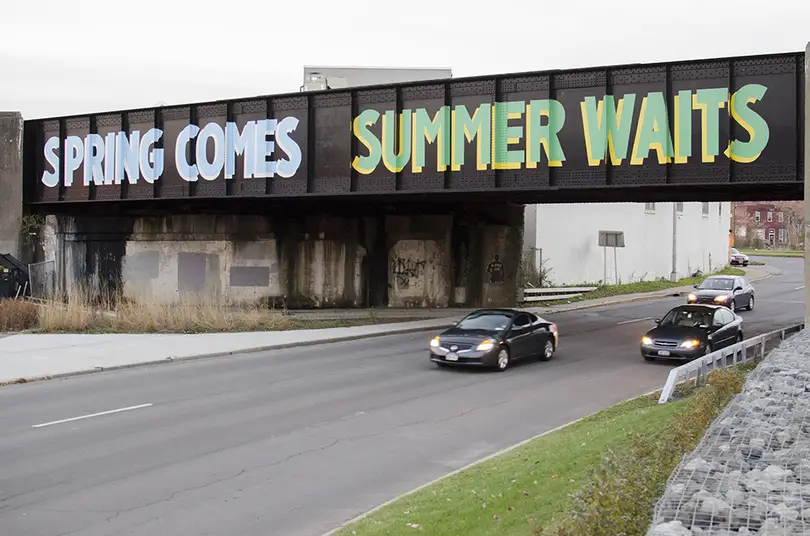

Only recently have artistic hubs like Seattle, New York City, San Francisco and even Syracuse begun to reintroduce hand-painted signs back into the market. The Red House itself sits flanked by Steve Powers’ “Love Letters to Syracuse,” a graffiti mural painted on the train trestles over West Fayette and West streets. The signs express what Syracuse residents love and hate about their neighborhood.

“The whole idea was, ‘How do we use art to disrupt this terrible rusty barrier?’” said Maarten Jacobs, director of the Near Westside Initiative. “And at the same time, we wanted to use Syracuse voices to dictate what messages go on the bridges.”

The mural is an example of creative space-making, Jacobs said, a philosophy that attracts new people to a community through a sense of activity and vibrancy. And the more Syracuse can infuse art into its neighborhoods, “the better chance it has of coming alive again,” Jacobs said.

In addition to the initiatives on the Near Westside, the art studio Echo, located on the Northside, has been contributing to urban development. The collective is used to attract artists and new residents to Syracuse, said Brendan Rose, one of the founders of Echo.

The studio has only been around for about a year and a half, but it has already built things like bike racks and benches, which are placed throughout the city.

“When you have people working on things with a certain degree of craft and integrity, then things tend to last,” Rose said. “So then you have a more sustainable urban environment where the history is there, and there are things for people to hold onto and understand about their place. When that craft isn’t there, things fall apart.”

Just like the attitudes of the artists in the documentary, Levine, Jacobs and Rose each have optimistic outlooks for the cities like Syracuse that are taking steps to infuse a new energy into the area.

“Implementing permanence for residents in a community literally is as easy as investing in a storefront or a wall and creating good signage,” Levine said. “That art and creativity keeps people.”

Published on November 5, 2013 at 1:47 am

Contact Joe: [email protected] | @joeinfantino