A voice that echoed: Fifty years after JFK’s assassination, alumni remember his 1957 commencement address at SU

Warren Kimble wishes he had a photograph of John F. Kennedy handing him his diploma from Syracuse University.

As class president, Kimble accepted the diploma for his class from the commencement speaker at graduation. In 1957, that speaker was Kennedy, then a junior senator for Massachusetts and rising political star. Kimble said he wants a photograph of his brief interaction with the future president as a legacy for his children, but has never succeeded in finding one.

Graduates from the class of 1957 said they remember June 3, 1957, for the excitement of graduation more than for Kennedy’s speech. But they vividly remember Nov. 22, 1963, when the news broke that Kennedy had been shot.

Kennedy was assassinated 50 years ago Friday while he rode through Dallas in a presidential motorcade. The news of the shooting, Lee Harvey Oswald’s arrest and Oswald’s murder two days later by nightclub owner Jack Ruby held the nation in thrall.

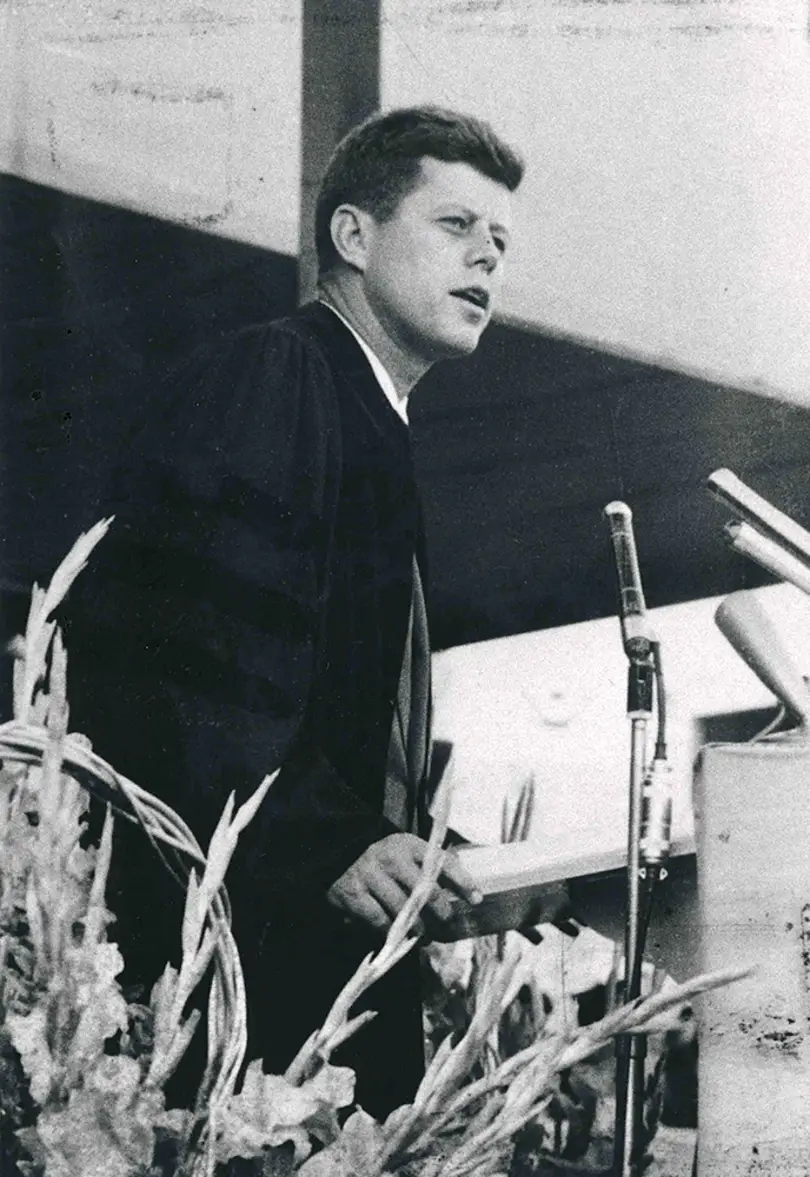

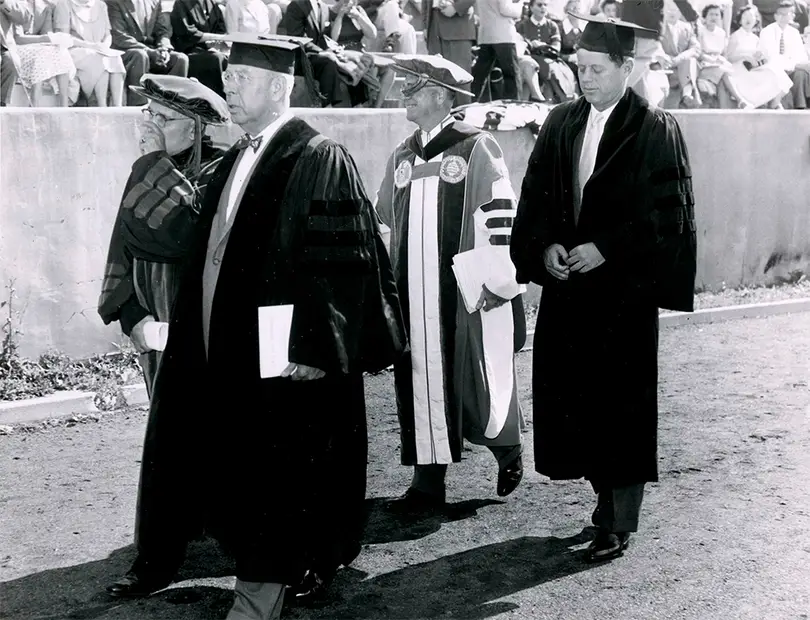

But before Kennedy’s assassination gripped the country — before he even acknowledged plans for a White House bid — he held the attention of about 5,000 SU graduates, family members and friends in Archbold Stadium.

Alumni said the announcement of Kennedy as commencement speaker failed to spark much of a political reaction on campus, since most students were more interested in graduation than the speaker.

Culver Barr, a political science major at the time, closely followed the elections of 1952 and 1956, and was interested to hear Kennedy speak because he knew Kennedy had almost become the Democrats’ 1956 vice presidential candidate.

From his seat near the middle of the stadium, Barr could recognize Kennedy as the man he’d seen on television.

Kennedy moved between earnestness and humor as he made small jabs at both political parties between the serious points of his speech. The laughter in Archbold Stadium sometimes drowned out the next lines of Kennedy’s speech, Barr said, especially when he made a remark about “beautiful Onondaga lake,” unaware that “it was a local joke at the time, the lake was pretty much like thick gravy.”

Kennedy’s speech focused mostly on a serious message: encouraging the 1,627 graduates present to put the skills they’d gained in higher education into politics. He urged SU’s graduates to close the gap between the academic and political arenas by using their knowledge to tackle real-world social issues.

Barr said the crowd received Kennedy’s speech, which was mostly nonpartisan and inspirational, attentively and respectfully. But the speech disappointed Barbara Caramella Regnell, who studied speech and drama at SU.

“I was upset. I had a feeling he wasn’t really talking to us, he was talking to potential voters,” she said. “And I was disappointed.”

Marcy Larson Street, Regnell’s friend and fellow sorority sister in Alpha Chi Omega, took a different view.

Initially, Street said, she was uninterested in the commencement speech, and mostly hoped that Kennedy’s speech would be brief. But once he began, she said, “I found myself hanging on his every word.”

Street, another speech and drama student, said she was struck by Kennedy’s skill as a speaker and his memorable call to action.

“When he ran for president in 1960, a lot of people really didn’t know who he was,” she said. “But I’ll tell you, every single person from the class of ’57 at Syracuse knew who he was.”

SU’s graduates of the class of 1957 might have had differing reactions to Kennedy’s speech. But the same word was used to describe their emotions when they heard of his assassination: “shocked.”

When Kennedy was assassinated in 1963, Kimble was the first in his office to hear. He used to listen to the radio through earphones as he worked in advertising design in an art studio in New Jersey. Since no one else in the office listened to the radio at work, Kimble became the bearer of bad news.

“I heard the news and went into the different offices and told them, and everybody was just devastated and couldn’t believe it,” he said. “I was shocked, just as I was at 9/11 watching television that day.”

Barr was in the dentist’s chair when the news broke.

He was chatting with the dentist, a friend, when a hygienist who’d heard the news on the radio rushed in to tell them the president had been shot. “Like everyone else, we were stunned,” Barr said. He left without having any dental work done to go watch the news unfold on TV.

“People were walking around in downtown Rochester, just everybody saying ‘Isn’t that terrible, isn’t that terrible,’” he said. “Nothing was done for the rest of the day but try to find out what had really happened.”

Street heard about the shooting while she was at home feeding her 1-year-old child. She immediately called her husband, who worked at Reader’s Digest, to break the news to the reporting staff that that the president had been shot.

Fifteen minutes later, she called again to tell her husband that the president was dead. But by then, his entire office was following the news on the radio.

That Sunday, Street sang in the church choir in a service that had become a memorial to Kennedy. As the choir exited the church they tearfully sang “America the Beautiful” rather than a hymn. Street recalls being struck by the lines they sang: “O beautiful for heroes proved in liberating strife, who more than self their country loved and mercy more than life.”

Like Street, Regnell first saw the news of Kennedy’s assassination on TV, as she was ironing in her home at an army base in Fort Rucker, Ala. “I was so shocked,” she said. “I just felt very, very bad about the whole thing.”

The nonstop assassination coverage strongly affected her two young sons, as well, as she soon found out when she saw her 3-year-old son and his friend playing with her 8-month-old son in the backyard. When she asked the boys what they were doing, they replied, “We’re playing President Kennedy. We’re gonna bury Will.”

The three days of coverage helped form the legacy of Kennedy’s administration as a modern Camelot, said Margaret Susan Thompson, an associate professor of history and political science in the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs.

“He’d been elected by 120,000 votes. Barely won. It was one of the closest elections in American history,” she said. But in surveys conducted within 10 days of his death, more than 60 percent of people said they voted for Kennedy, Thompson said.

“Now, it wasn’t that they were lying,” Thompson said. “It was that, I think, so many Americans couldn’t believe that they wouldn’t have voted for this amazing guy after watching all that nonstop eulogizing, and it wasn’t just coverage, it was eulogizing.”

Kimble and Regnell both used the word “Camelot” to describe Kennedy’s presidency, a term Thompson said was never used to describe his administration until Jacqueline Kennedy brought it up in an interview a week after her husband died.

But regardless of how Kennedy came to be remembered in the nation at large, he has a more personal legacy for some SU graduates who heard him speak on a hot afternoon in 1957.

Kimble said although he didn’t immediately realize it in the midst of graduation excitement, Kennedy’s speech made a lasting impression.

“It made me feel that I should do something other than just get a job,” Kimble said. And, in retrospect, he believes Kennedy’s speech helped inspire his work founding an artists’ guild that seeks to promote the arts and uplift his community of Brandon, Vt.

“I wanted to do good in the world and I think I’ve always thought about that and accomplished that in my way,” he said. “And that goes back to that day in 1957. I think I heard it.”

Published on November 21, 2013 at 12:17 am

Contact Maggie: [email protected]