Syracuse RBI program exposes inner-city kids to baseball

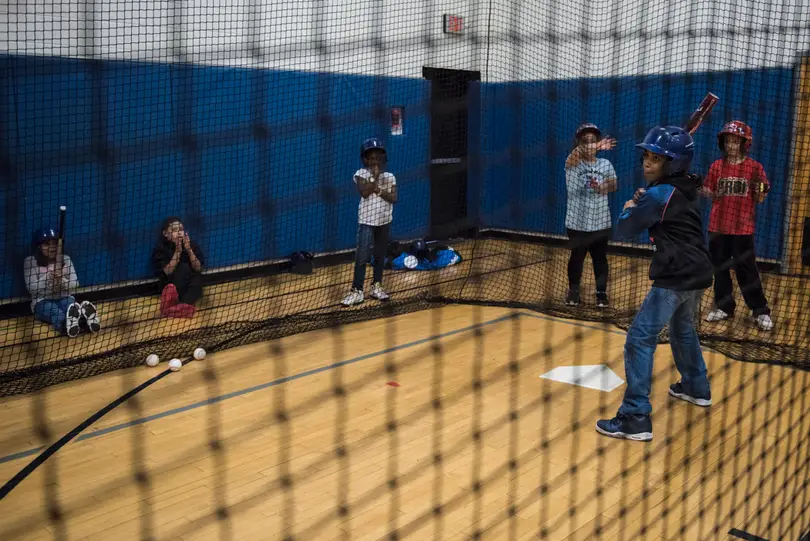

A line of boys and girls stood outside of the batting cage, clapping their hands to the beat of every ding that echoed in the gym at the Boys & Girls Club of Syracuse. Each time ball met bat, they chanted and jumped in jubilation. For many, moments such as these provide security.

Late last week, a dozen kids ages 9 to 12 met at the club on Hamilton Street, where the Reviving Baseball in Inner Cities (RBI) of Syracuse sets up a batting cage and holds its practices. The kids giggled throughout the 90-minute session, one of many since they began the biweekly practices last fall. As temperatures warm up in the coming weeks, they will head outside and begin the 2017 season, which marks the program’s 13th in Syracuse.

A Major League Baseball youth program, RBI is designed to increase participation and interest in baseball and softball among underserved youth — at no cost to them. Since its inception in 2005, Syracuse RBI bulged from 15 participants to 80 in 2009. By 2012 that number shot up to 150 and, last summer, reached 286. This year, director Steve Barnum expects more than 400 kids over several age groups to take the field — what would be the program’s largest growth over one year.

“It’s incredible. Baseball is something these kids would never get to do otherwise,” said Barnum, a former high school coach who started the program with one team.

Thirty-four volunteer coaches assist with RBI, giving baseball and softball opportunities to Syracuse’s inner-city kids. Most come from lower income families, grow up in single-parent households or do not live with either of their parents.

Twenty-six years ago, the MLB took RBI under its wing and spread the program to New York, St. Louis and Kansas City. It now has more than 260,000 players in more than 300 baseball and softball programs across the United States — Philadelphia, San Diego, Miami, to name a few — as well as countries like Canada, Dominican Republic, Curacao and Colombia.

Several RBI alumni play in the Majors now, including Baltimore Orioles star outfielder Adam Jones, Orioles third baseman Manny Machado, Los Angeles Dodgers catcher Yasmani Grandal and Philadelphia Phillies No. 1 prospect J.P. Crawford. MLB clubs have drafted more than 200 RBI participants, including 13 selected in 2014 alone. The league has donated more than $30 million to fund RBI programs.

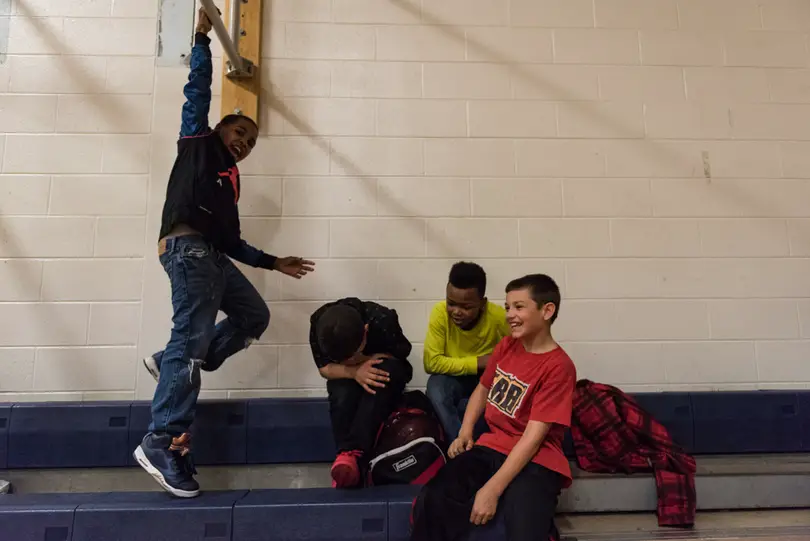

While many players thrive on the field, RBI’s focus is to keep kids off the streets, teach life lessons through organized games and boost diversity in a sport that lacks it.

“Instead of violence on the streets, they’re able to be in a team environment and have fun playing baseball,” said Steve Theetge, a Syracuse RBI alumnus and current Bryant University starting pitcher. “It goes overlooked. People think of it as just a baseball program or a sport. It’s a lot more than that.”

Former MLB scout John Young founded the program in the 1980s when he noticed few black players playing professionally. RBI leaders say rekindling passion for baseball among black kids in Syracuse and cities like it rests on programs such as RBI.

Only about 8 percent of active major league baseball players are black, according to the MLB. That’s about half of the percentage 30 years ago. And of the league’s 30 teams, Dusty Baker of the Washington Nationals is the lone black manager.

Which means RBI is especially important in Syracuse. In 2015, Syracuse had the highest rate of extreme poverty concentrated among blacks and Hispanics out of the nation’s 100 largest metropolitan areas. About half of the city’s children live in poverty.

Barnum said a couple of hours on the baseball diamond could refocus youth.

“Playing baseball,” Barnum said, “it takes kids away from something else they could have gotten into on the streets.”

Theetge, the Syracuse RBI alumnus, credits much of his success to his roots with the program. Some professional scouts say the 2016 freshman All-American has one of the best changeups in college baseball. That’s because, per RBI rules, he could throw only fastballs and changeups — no breaking balls, which can damage a teenager’s arm — until he turned 16.

Theetge’s father, who shares the same name, remembers walking door-to-door on Saturday afternoons, asking for donations. He and his son collected loose cans and traded them in for extra cash to pay for umpires and uniforms. Theetge’s father volunteers about 40 hours per week maintaining the field, throwing batting practice and coaching teams. He once paid $1,200 out of his own pocket for an old van, which he used to drive kids to games because many of the inner-city participants’ families do not own cars.

The Syracuse RBI program has more than tripled since 2009. This fall, it’ll send Cicero-North Syracuse High School senior Luke Dziados to Binghamton University, their second alumnus to attend Division I school. With no signs of slowing down, Syracuse RBI hopes to keep growing. Last summer, the Syracuse Chiefs, the minor-league team that donates gloves and bats to RBI, held a community night highlighting the program. Le Moyne College ran clinics for RBI players last fall and Onondaga Community College has expressed similar interest for 2017.

“We’re still way short to what the suburban kids get for practicing baseball,” Theetge said. “But we had no money, no funding. Now we’re an established, credible league where it’s about getting baseball and education together.”

Published on April 10, 2017 at 10:42 pm

Contact Matthew: [email protected] | @MatthewGut21