‘Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere’: Fifty years later, Syracuse residents reflect on SU’s role in Civil Rights Movement

In the early morning of Sept. 18, 1963, eight Syracuse University students stood side-by-side outside of the Syracuse City Courthouse. Waiting for their arraignment, they began to softly sing, “We Shall Overcome.”

As they moved inside the courtroom, their melody grew louder. Despite their lawyers’ requests, the students would not be silent. They wanted their voices to be heard.

It was amid the civil rights movement, and the eight students had been arrested during a protest against Urban Renewal – a federally funded program that discriminated against black residents.

Fifty years later, the movement in Syracuse is still recognized as distinct because of the role SU’s faculty and students, both black and white, played in speaking up and addressing the racism that existed in the city.

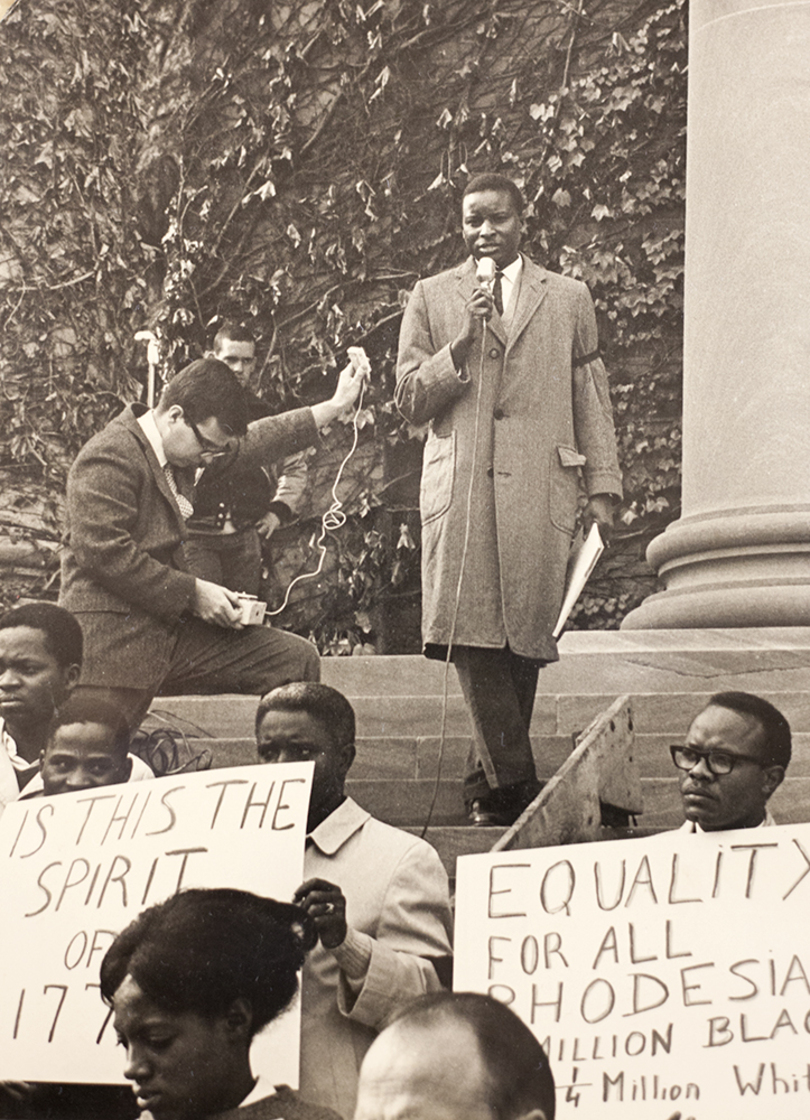

Congress for Racial Equality, which consisted of professors, students and local residents, was one of the more aggressive civil rights groups in Syracuse in terms of protests and marches, said Dennis Connors, a history curator at the Onondaga Historical Association. The group mainly protested that blacks were not allowed to integrate into better parts of the city.

“I think some of the faculty were very passionate about these civil rights issues, and that sort of communicated to some of their students,” Connors said. “Individuals associated with the university, both faculty and students, were a catalyst for motivating some of the African-Americans in the community and to get them worked up about civil rights.”

He said SU faculty tended to have a wider appreciation and understanding of the national civil rights movement. Because of this, many faculty members wanted to bring the activism in the South up to Syracuse.

“They were really saying ‘We’re not Birmingham or Selma, Ala., but that does not mean that there is not discrimination going on in Syracuse,’” Connors said.

—

When Clarence “Junie” Dunham was growing up in Syracuse in the 1950s, his grandmother warned him never go to the north side of the city. It wasn’t safe for blacks to be in that part of town, she said.

“That’s what Syracuse was like at the time. It was very, very prejudiced at the time,” Dunham said.

Part of this prejudice was manifested in Syracuse’s Urban Renewal. The project called for the area between State Street and the university to be re-developed as a government complex, cultural center and high-rise residential neighborhood.

But standing in the way of city planners’ vision was the 15th ward, which some city residents considered an overcrowded slum. When the planners decided to eliminate the ward to make room for the new buildings, 75 percent of the local population, 488 families, were relocated, according to the Onondaga Historical Association Archives.

Of those families, 326 were black.

“Urban Renewal devastated the black areas,” said Dunham, who grew up in the 15th ward.

Dunham said a majority of the black families struggled to find new housing because few areas in Syracuse allowed blacks to rent or buy property.

A newlywed with two young daughters, Dunham said he called dozens of different places to rent a house in Syracuse. When he told the landlords he was black, each landlord then told him there weren’t any houses available.

“Blacks really couldn’t do too much,” he said. “They couldn’t own anything.”

In addition to housing, Dunham said it was extremely hard for blacks to find jobs in the city.

According to a 1963 report by a team of SU educators, there was little black representation in many occupations in Syracuse.

“One must either assume that the employability of the Syracuse Negroes in these jobs is less than in other cities or that discrimination against the Negro is more widely practiced in this city than elsewhere in upstate New York,” stated the report.

It also stated that 2.7 percent of black income-earners in Syracuse made more than $6,000 per year in 1960. In New York City, this percentage was 4.5 percent; Buffalo, 5.2 percent; Rochester, 3.7 percent; and the Albany-Schenectady-Troy area, 3.5 percent.

Various civil rights groups advocated for better employment for African-Americans.

Marshall Nelson, a Syracuse resident and member of the Catholic Interracial Council, worked with Congress for Racial Equality to picket the Niagara Mohawk Corporation, the only power company in Syracuse at the time. Protesters argued the company had an intentionally low representation of blacks.

The company had about 16,000 employees in the state of New York, Nelson said. Twenty were black.

Greta Jones, a Syracuse resident who also grew up in the 15th ward in the 1960s, said the racial tension that existed in the city became a part of life.

“I guess when you live with it for so long, you start to hardly pay attention to it,” Jones said. “You just sort of … endure it.”

—

The civil rights movement was also active at SU, particularly with CORE protests, said Connors, the history curator. The white leadership in Syracuse pressured the university to crack down on controlling the students involved.

The CORE protests also created financial consequences for SU. During the time of the pickets in 1963, the university was in the middle of a $76 million fundraising campaign. Several local businessmen who donated money in past years said they wouldn’t contribute money unless the university did “something about its personnel involved in demonstration,” according to a Sept. 18, 1963, article in The Herald Journal.

On Sept. 23 of that year, SU Vice President Eric Faigle spoke on behalf of the administration, saying any graduate or undergraduate student arrested or detained by police in a legal action would immediately be placed on “disciplinary probation.”

At the time, 51 students, nine faculty members and 18 community members had already been arrested. About one month later, the number totaled 100 people.

To retaliate, 150 students protested the policy by picketing on the Quad. On Oct. 7, the Joint Student Government issued a statement to Faigle, asking that the automatic disciplinary probation policy be withdrawn.

That same day, Faigle told The Daily Orange the policy would be withdrawn immediately.

—

But as to why students participated in the civil rights movement, Ronald Corwin, an SU CORE student organizer, told The Daily Orange in 1963 that it was their right as citizens to speak up.

“The worst thing is not hate; the worst thing is not prejudice,” Corwin said. “The most appalling thing is silence.”

Published on February 21, 2013 at 12:31 am

Contact Meredith: [email protected] | @MerNewman93