University, local communities examine present, future of Connective Corridor

/ The Daily Orange

It was an imposing ivory tower. It was a fading manufacturing town. It was the same city, worlds apart.

“When you get away a distance from the downtown area and get up on a hill, you look out at the skyline and it looks like there are two cities side by side,” said Dennis Connors, history curator at the Onondaga Historical Association, imagining himself looking down on the city of Syracuse.

The Connective Corridor, introduced by Syracuse University Chancellor Nancy Cantor in 2005, aims to bring the university and downtown closer through a three-phase transportation and streetscape improvement project. It encourages travel between the two areas through public transportation, artwork and community involvement.

The $42.5 million mission is an ambitious one: Transforming a rust belt city into a robust, environmentally conscious urban center. But the city is beginning to see the results.

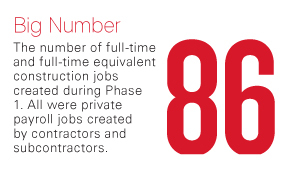

The first phase of construction ended this fall, turning University Avenue into a two-way street and introducing a green bike path and red streetscape improvements from the edge of campus to East Genesee Street. The project was awarded the “Transportation Project of the Year” by the Institute of Transportation Engineers New York Upstate Section.

“When you look at it, you do realize that it’s more than just a bus route and it’s more than just a streetscape,” said Linda Dickerson Hartsock, who joined the project as director of the Office of Community Engagement and Economic Development at SU and overseer of the Corridor in February.

The effort is billed as the city’s largest public works project in more than 30 years, but as the project enters its second phase, some campus and community members continue to question the Corridor’s function and how it will effectively push Syracuse into the 21st century.

Counteracting I-81

There was a growing sense that the grandeur of the city — once a thriving industrial hub — began to dull after a number of industrial corporations began departing the city several decades ago, said Connors at the Onondaga Historical Association.

Activity on the Hill boomed while industry and activity downtown slowed. Non-manufacturing jobs in medical and higher education fields dominated, usurping manufacturing as the largest industry in the area.

As the city attempts to strike a balance between identities, SU’s relationship with the city of Syracuse has also undergone change since Cantor’s 2004 arrival at the university and the introduction of the Corridor concept.

SU’s reputation as an “ivory tower,” removed from city life, has gradually subsided since Cantor’s arrival, said Rob Simpson, president of CenterState CEO and co-chair with Cantor on the Central New York Regional Economic Development Council.

Cantor said she came to Syracuse conscious of the separation. After a year of discussions with campus, city and government members, the university introduced the Corridor concept. The university established its downtown presence in 2006, restoring the Dunk & Bright Furniture warehouse at a cost of $13.9 million as workspace for architecture and design students, now known as The Warehouse.

From an urban planning standpoint, the Corridor counteracts the physical divide between SU and downtown created by Interstate 81. The overpass and the cluster of on-and-off ramps create unfriendly pedestrian walkways because of the fast-moving I-81 traffic.

An appealing urban center is also fundamental to attract students and professionals to the area — people are less inclined to work and live in dingier cities, Simpson said.

“The city depends on the university,” he said. “I think the university depends on the city.”

Money, money, maintenance

The Corridor is among a number of growing “innovation districts,” urban areas that combine art, public transportation and green infrastructure to encourage economic growth and community stability.

The group New Jersey Future studied Syracuse and three other cities this past summer as part of a strategic plan designed to guide economic development. Its research determined successful districts are formed through collaboration of higher education, private business and government. Each party’s level of involvement can vary between districts.

“These things are kind of organic, it’s whoever picks up the charge to make it happen,” said Chris Sturm, senior director of state policy at New Jersey Future.

Hartsock identifies SU’s role in the Corridor as “the catalyst for finding and assembling resources for the city.”

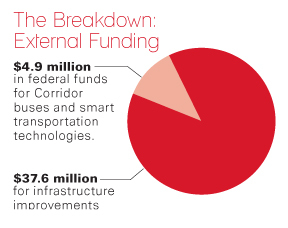

SU’s Office of Community Engagement and Economic Development procured the $42.5 million in external funding needed for the construction of the Corridor. Of those millions, $37.6 million is for infrastructure improvements and $4.9 million is in federal funds for Corridor buses and smart transportation technologies. Hartsock said officials are expecting spending for phase one construction to meet the phase’s budget.

SU officials say no tuition is spent on the Corridor. Hartsock said some of the worst feedback she has heard regarding the Corridor hinges on the fact that community members struggle with understanding the purpose of the Corridor and where the money is coming from, especially since several years were spent at the drawing board.

The project’s first four years were largely spent constructing and designing the physical aspects of the Corridor, such as the bike lanes, said Marilyn Higgins, vice president of community engagement and economic development.

Planners and designers had to make some concessions to comply with Federal Highway Commission regulations, leading to bumps along the road. Designers were insistent that bike lanes should be the trademark Corridor red, but new federal law requires bike lanes to be painted green.

As the Corridor moves forward, local businesses and city government will begin to play larger roles, especially financially. Money and services dedicated to maintaining the route will be provided by the city of Syracuse and Onondaga County.

SU will not be responsible for future care of the Corridor, say university officials.

Merike Treier, executive director of the Downtown Committee of Syracuse, said a plan to maintain newly installed items along the Corridor route, such as trash cans and trees, is being discussed. The city has agreed to plow the bike lanes and maintain new lighting along the route. The county will be responsible for maintaining environmentally friendly infrastructure.

For the maintenance responsibilities that don’t fall in either arena, including watering, weeding and pruning trees, Treier said will continue to work with property owners to develop a maintenance plan.

Owen Kerney, who is working with Treier and is deputy director of the city’s Bureau of Planning and Sustainability, said it is difficult to quantify how much it will cost to maintain the route.

“Taking over maintenance for the Corridor is not something the city can put a cost to,” Kerney said, although it will add more work and hours.

Investing in the university

Though grants cover construction, there are indirect costs and responsibilities associated with the university’s downtown initiatives.

SU pays the salaries of the five employees in the Office of Community Engagement and Economic Development, located in The Warehouse. More than 400 SU faculty members and students also spend time on the project, incorporating classroom lessons into Corridor projects.

To some, the Corridor initiative is seen as “eating up money resources that some people would rather see invested on campus,” said SU trustee and local resident Judy Mower. She said what money the university has invested into the Corridor has been “very small” in comparison to the grants that make the initiative possible.

Having an inviting downtown helps the university attract students and professors interested in the innovative academic opportunities, Mower said.

“It’s like a terrific sandbox for professors who are working in those fields and their students,” Mower said.

But faculty attribute the focus on downtown involvement as the reason why SU has fallen in university rankings. In the mid-‘90s, before Cantor’s arrival in 2004, U.S. News & World Report ranked SU in the 40s. It is now ranked No. 58 and was recently ranked in the 60s.

Professors who question the purpose of SU’s involvement in the community also point to SU’s 2010 departure from the Association of American Universities, a select group of the top research institutions. Unlike a typical AAU university, SU does not have a medical school and instead finds strength in areas like the fine arts, communications or public policy, areas included in SU’s downtown programming.

Jeffrey Stonecash, a political science professor at SU and a self-described skeptic of the Corridor from the start, said despite the trumpeting he has heard regarding the project, he has yet to see the results, and he questions how the effects could be measured.

“Let’s stop promoting it as a great idea and see if it really works,” he said.

Cantor said she doesn’t feel the additional work in the city diminishes educational opportunities at the university. The Corridor turns away from traditional academia and emphasizes innovation and collaboration in the city, she said.

“You can see that that’s a new wave of thinking about collaborative work that goes across sectors where people get to push their disciplines,” she said.

Down on East Genesee Street, the staff at the Community Folk Art Center hopes the Corridor will pull more people into the gallery, which hosts music performances and exhibits relating to the African Diaspora.

Kheli Willetts, executive director of the CFAC and an assistant professor of African American studies at SU, said she doesn’t see enough students venturing off the hill.

“We walk around campus, but we generally don’t walk down, at least not past Marshall Street,” Willets said.

The Connective Corridor bus route —a free bus route that starts at Goldstein Student Center on South Campus and weaves its way downtown to The Warehouse — is meant to encourage students to leave the Hill. The university pays Centro $450,000 a year to run the Connective Corridor bus route and other SU routes.

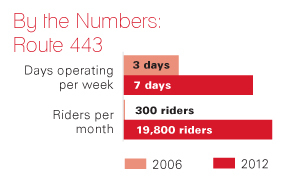

When the Corridor route was first introduced in fall 2006, it ran three days a week and picked up between 200 to 300 riders per month, said Steve Koegel, director of marketing and communications at Centro. The bus route now averages about 19,800 riders per month, Koegel said, attributing the uptick to an increased awareness of the Corridor and routing adjustments.

Ridership is calculated based off SU’s academic year, on a September to May basis. Ninety percent of ridership is students, many of whom need the route to access classes in The Warehouse.

Still, there are times when the bus is empty or near empty. Students complain the bus can be unreliable and choose to drive downtown. College of Visual and Performing Arts students going from campus to The Warehouse say they would prefer a shuttle that goes directly from main campus to The Warehouse.

But that would defeat the purpose of the Corridor.

‘Growing pains’

Though the Corridor’s long-term influence in bringing business to the recently completed East Genesee Street area is yet to be seen, Gary Brothers, an owner of a pharmacy located on East Genesee, said the business took a financial hit during the area construction.

Customers were forced to search for parking amid blocked-off or torn-up sidewalks and roads. Down the street, Strong Hearts Cafe, a vegan-friendly cafe located across Forman Park, a water main burst and shut off the restaurant’s water supply.

Heading into phase two and three, downtown businesses have been prepped about possible disruptions to business, said Merike Treier, executive director of the Downtown Committee of Syracuse.

Business owners do say the completed construction has made the area more aesthetically pleasing. A total of $625,000 in facade improvement grants, or money set aside for businesses to make minor improvements to storefronts, was made available through the project. Strong Hearts Café will make minor improvements with outdoor seating.

Hailed as one of the project’s major successes to date, Forman Park is outfitted with red benches and a sign marking the park’s entrance in the red, wiry Corridor text. Opposite the park, a fence reads, “Use your feet. Use your imagination. Use parks. Use your eyes.” in the same font.

Frank Cetera, president of the Near Westside Business Association, said he’s heard from businesses along East Genesee Street about construction issues. But as project construction inches closer to downtown and the Near Westside, the short-term inconvenience will be worth it in the long run.

“It’s growing pains. Anything you experience when you’re going through development is accompanied by growing pains. It’s unavoidable. And it’s necessary.”

Up next

With Cantor’s announcement that she will depart SU when her contract expires in 2014, there is a question of whether or how the university’s role with the Corridor will change. Cantor is seen as the force behind the idea, and faculty suggest it will be difficult for the next chancellor to not embrace the Corridor.

But Cantor is confident the Corridor’s mission will continue after her departure.

“It’s happening. We’re seeing that. We’re seeing public works, lots of different engagement,” she said. “We want to really continue that and there’s lots of groups involved, so I’m positive that will continue.”

Officials at the Corridor show no signs of slowing down. Work on the city’s civic strip, where the Oncenter and the Everson Museum of Art intersect with the Corridor, to introduce new signage and lighting will be done in the next year. City officials hope the changes will help tourism.

Hartsock said she has worked to continue well-established relationships with departments at SU, but she would like to expand student engagement in the Corridor. She said she would love to see business students help do a real estate inventory of the buildings along the Corridor and biology majors work on the Onondaga Creekwalk.

The function and purpose of the Corridor remains in flux, as officials look for the best way to achieve the mission of connecting the Hill to downtown through changing thoughts and landmarks.

“We try to make it a laboratory, which means we’re experimenting,” Hartsock said. “And some things work and some things don’t work as well.”

Published on December 5, 2012 at 5:10 am

Contact Debbie: [email protected] | @debbietruong